Introductions

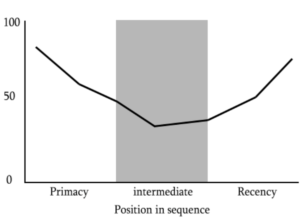

The human mind has a tendency to focus on the first and last things in a series. Social scientists call this the serial-position effect, a combination of the primacy effect (remembering the first thing one hears) and the recency effect (remembering the last thing one hears).[1][2] In practical terms, it means that for speeches, introductions and conclusions are extremely important.

Purpose of a Speech Introduction

For those new to public speaking, an introduction may seem like an afterthought to a well-researched and organized speech. Seasoned speakers can tell you, though, that having a well-thought-out and well-delivered introduction is one of the most important aspects of a successful speech. The introduction is where the audience makes a decision about you and your topic. Although the introduction takes no longer than 10–15% of your total speech time, it must be thoughtfully constructed in order to convince your audience that you and your topic are worth listening to.

An introduction must achieve five goals in a short amount of time:

Goal 1: Get the audience’s attention

Although you might be thinking of nothing but your speech in the moments before and during it, your audience is likely thinking about something else. Even though you, the speaker, are seemingly the only thing standing in front of them and speaking, you must wade through a sea of distractions to actually get their undivided attention.

Goal 2: Establish credibility

Establishing credibility through your introduction demands a nuanced combination of both verbal and nonverbal communication that demonstrates the speaker’s competence, trustworthiness, caring, and goodwill toward the audience members.

Competence refers to the level of expertise or knowledge the audience perceives the speaker to have in the subject matter they are discussing. It can be established when the speaker has a legitimate title and/or expertise in the subject matter.

Trustworthiness refers to whether the audience perceives the speaker as honest. Unfortunately, sometimes an audience will remain skeptical due to the topic or previous perceptions of the speaker. However, a speaker can work to build trustworthiness by using credible, unbiased sources, and fact checking. A trustworthy speaker also will avoid using information out of context and will work to make all information logical.

Caring and goodwill refers to how the speaker is perceived as caring about the audience and having their best interest at heart, rather than trying to manipulate the audience. Thoughtful audience analysis to create relevant examples and arguments can establish caring and goodwill.

Goal 3: Provide a reason to listen

If your initial attention getting strategy was successful, you now must convince the audience to continue paying attention to your speech by illustrating the importance, timeliness, and relevance of your topic in direct relation to them. A good speaker will use audience analysis to discover ways in which the topic directly impacts the audience.

Goal 4: Reveal the Main Idea

The introduction should quickly get to the point by simply and succinctly stating the thesis or central idea of the speech. If the audience is unclear about your main idea, they are likely to stop listening, just as you might stop listening to someone is not making a clear point. You should be able to create a simple sentence that draws the audience’s attention to the singular purpose and thesis of the speech.

Goal 5: Preview main points

An introduction should end with a clear preview of the main points of the speech, offered in the order in which you intend to present them in the speech.

It’s important to use concise language and to only preview the names of your main points, avoiding the mention of any subpoints or supporting details. Imagine your preview is a road sign showing the major city in that direction, not all the smaller stops along the way.

It’s also important to preview the main points in the order that they will be presented in the speech, to prepare the audience for the flow of the speech, and to help the audience find their place in case of a momentary day dream.

Types of Introductory Attention-Getters

The first thing an audience hears in your speech should always be the attention-getter. There are several ways to get the attention of an audience, but not all are effective. While it might be tempting to be loud or to wave your arms, those tactics will provide only a temporary distraction to your audience and will likely hurt your credibility. Unless your attention-getter is relevant to your speech, your audience may not devote any further attention than simply recognizing that you are there.

An effective attention-getter serves three functions:

- Sets the tone for your speech

- Acknowledges and appeals to your audience

- Provides a reason for your audience to keep listening, a “teaser” for your topic

There are eight useful attention-getting devices that fulfill the three attention-getter functions when used well. Some are more effective than others in particular situations, which is where your audience analysis is important. Many can be used together and/or used with humor. When deciding which to use, consider the amount of time you have to prepare your speech, whether your audience will likely need winning over, and how familiar they may already be with your topic.

Type #1: Rhetorical question

A rhetorical question is one to which no reply is expected, but instead invites the audience to consider something.

- “If you had to eat the same thing for every meal, every day – what would it be? In the Republic of Korea, that answer is easy: kimchi. In fact, that is exactly how often it is eaten.”

Type #2: Quotation

This attention-getting device uses the words of another person that relate directly to your topic. If the person you are quoting is not well known, it is a good idea to provide information of why that person is relevant in the context of your speech.

- “Famous American historian Donna Gabbacia stated, ‘Humans cling tenaciously to familiar foods because they become associated with nearly every dimension of human social and cultural life. . . . Eating habits both symbolize and mark the boundaries of cultures.’ Nothing exemplifies her words more than the national dish of Korea, kimchi.”

Type #3: Refer to the audience

When using this attention getting device, the speaker shows their understanding of the audience by drawing attention to a unique quality the audience shares that should make your topic interesting to them.

- “Here in Philadelphia, we probably all have eaten cheesesteak. But even though we have the 8th highest Korean population in the U.S., have you ever eaten kimchi?”

Type #4: Refer to a recent, current, or historical event

Referring to a recent, current, or historical event as your attention-getting device can help the audience gain awareness of how relevant your topic is in today’s world. It can serve as an emotional appeal as it summons the feelings that the audience members associate with the given event.

- “As we in the United States begin planning our Thanksgiving dinner, more than 3,000 people will gather in Seoul to cook kimchi together for the city’s annual festival.”

Type #5: Hypothetical Scenario

Similar to a rhetorical question, the goal of using a hypothetical scenario is to engage the audience by asking them to consider something. What makes a hypothetical scenario more effective than a rhetorical question is that the audience members are asked to be the protagonist in a story, which evokes emotions, suspense, and identification.

- “Imagine sitting down after a long day to eat a well-deserved meal with your family, the table full of comfort food. Now, if you are sitting at a table in Korea – your comfort food is something that has been slowly fermenting for a year!”

Type #6: Anecdote: External or Personal

An anecdote is a very effective attention-getting device, using a real story or account of an interesting or humorous event. It can be an external story or account, or a story about yourself. If you are an expert, or have first-hand experience, an anecdote is an excellent way to show that you are credible from the very beginning. When using an anecdote in your introduction, you should ensure that it is brief and has a clear application to your topic.

- “When South Korea’s first astronaut, Ko San, blasts off April 8 aboard a Russian spaceship bound for the International Space Station, the beloved national dish [kimchi] will be on board. Three top government research institutes spent millions of dollars and several years perfecting a version of kimchi that would not turn dangerous when exposed to cosmic rays or other forms of radiation and would not put off non-Korean astronauts with its pungency.”

Type #7: Provocative Statement

A provocative statement makes an excellent, but sometimes challenging, attention-getting device. It is especially effective if the audience is already aware of your topic and may hold certain beliefs, attitudes, or knowledge about it. A provocative statement begins with a well-known fact about your topic, but then challenges that idea. This statement will pique the interest of your audience as well as challenge their own existing ideas about your topic.

- “Kimchi is well known as the national dish of Korea, eaten at every meal. However, the kimchi museum in Seoul claims that Korea’s neighbor across the Yellow Sea invented the national dish some 3,000 years ago.”

Type #8: Startling Statistic or Strange Fact

When considering a startling statistic as your attention-getting device, the goals should be to surprise and engage your audience. You can achieve the same goal by using a strange fact if you do not want to use numbers or statistics.

- Startling Statistic: “There are over 200 varieties of kimchi. It is both a condiment and a meal. It will preserve your health while burning you from the inside out. The average Korean eats 40 pounds of kimchi per year.”

- Strange Fact: “When the SARS pandemic tore through Asia, Korea was left untouched. The reason for that is . . . kimchi.”

Make sure to choose the best type of attention-getter for your speech’s purpose, audience, and context. If you are having trouble choosing, you can use the criteria below, but only with the understanding that choosing an attention-getter is a personal choice – you are the best person to determine how best to start your speech.

- Attention-Getters 1 to 2: may be useful for an audience that is already familiar and positively invested in your topic.

- Attention-Getters 3 to 5: may be useful for an audience that may not be as familiar or positively invested in your topic.

- Attention-Getters 6 to 8: may be useful for an audience that does not know about your topic or knows but disagrees with your thesis.

The following video provides examples of attention-getters:

You can view the transcript for “Examples of Attention Getters” here (opens in new window).

Here is the video with accurate captions: Examples of Attention Getters (opens in new window).

Writing and Revising the Introduction

Write an introduction, keeping in mind how important the introduction is. After you write your first draft of the introduction, revise it by asking and answering the following questions in order to evaluate the strength of your introduction and refine it as needed.

Question #1: How long is my introduction?

Your introduction should be no longer than 10–15% of your total speech. That means that in a five-minute speech, your introduction will last between 30 and 45 seconds. In a ten-minute speech, your introduction will last between 60 and 90 seconds.

Question #2: How effective is my attention-getter?

Although your speaking situation may only require a simple attention-getter, the best way to start your speech is with one of the highest order attention-getters: an anecdote, a provocative statement, or a startling statistic/strange fact. By moving up the echelon of attention-getting devices, you will entice the audience and bolster your own credibility in the process.

For example, you might start a speech about tea with a reference to flamingos:

“A startling fact: Since flamingos spend most of their time in water with high salt concentrations, they have to get fresh water from boiling geysers. The flamingo is one of the few animals who likes to drink water at a boiling point. Another, of course, is the human. I’m here today to talk about tea.”

Question #3: Have I adequately linked my attention-getter to my topic?

If you picture your introduction as a funnel, your attention-getter should filter into your topic and lead to your thesis through a logical sequence of ideas. Your attention-getter should be relevant to your topic by teasing or introducing the idea. After the attention-getter, you should then provide a more specific statement that narrows the focus onto your topic, and introduces your thesis.

Question #4: How strong is my thesis?

A strong thesis is clear, succinct, and simple. The audience should have no doubt what your topic is, the specific aspect of the topic that will be discussed, and your stance on it. You can make your thesis even stronger by swapping out any passive verbs in favor of active ones, paring down the wording, and drawing attention to your thesis by beginning it with a time indicator, such as “Today . . . .”

Question #5: Have I provided a reason to listen?

Your introduction should contain a significance statement either just before or just after your thesis that provides the importance, timeliness, and relevance of your topic in direct relation to your audience. Since the speaker generally chooses their own topic, the audience already knows that the topic is important to the speaker. Therefore, to bolster speaker credibility, use a reputable source to support this statement. Further, audience analysis should be used to illustrate how the topic impacts the audience members, whether socially, financially, ethically, medically, etc.

Question #6: How easy is it to recall my preview?

The last part of your introduction should be a simple preview of your main body points. A good preview is easy for the audience to identify and recall. Using time indicators such as first, next, and finally help the audience to clearly separate each main point in the preview. In addition, a great preview is short, creating names of one or two key words for each main point. Names can then be reworked with literary techniques such as rhyming, alliteration, and parallel structure to help the audience recall the tags. Finally, the main points should be stated in the same order they will be presented during the speech.

Question #7: How have I established my credibility?

Unfortunately, establishing credibility is not as easy as just being friendly, having a title, or simply telling an audience to trust you. Audience members have access to their own knowledge, experience, and research. As such, they likely trust themselves more that they will trust you. Further, even experts can be considered out-of-touch know-it-alls if they do not show an understanding of their audience’s experience and knowledge.

To establish credibility, a speaker needs to demonstrate competence, trustworthiness, and goodwill and caring toward the audience. Good speakers use every avenue available to establish from the very beginning and continue reinforcing their credibility.

- Nonverbal Credibility: appropriate dress for the occasion; using open, friendly, and appropriate facial expressions; displaying preparation and confidence; maintaining eye contact

- Verbal Credibility: using appropriate and relatable language, correct use of words

- Content Credibility: using credible sources, showing knowledge of audience experience and goals, using logical reasoning