Language and Style

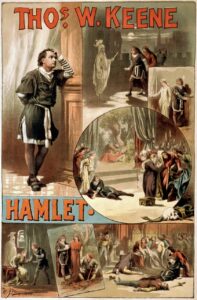

What kind of language should you use in your speech? Should your words be blunt and to the point? Or should you use soaring rhetoric and lofty ideas? Well, it depends on the topic, audience, and context of your speech. As Shakespeare puts it, “Suit the action to the word and the word to the action” (Hamlet Act 3, Scene 2).

No matter what kind of language you decide to use in your speech, certain things will always be true:

-

language must be appropriate for oral delivery (rather than written style)

-

language should be as concrete and meaningful to your audience as possible

-

avoid exclusionary, inappropriate, and inaccurate language

Oral versus Written Style

In a public speaking class, you will likely be asked to turn in an outline rather than a manuscript because speeches are oral presentations and not intended to be written text.

Although we’ve seen many speeches delivered from a teleprompter, it is important to remember that those speeches are usually written by professional speechwriters, who are familiar with the differences between written and spoken communication. For newer speakers who are writing their own speeches, identifying the differences between oral and written style is an important key to a successful speech.

Oral communication is characterized by a higher level of immediacy and a lower level of retention than written communication; therefore, it’s important to consider the following adaptations between oral and written style.

Personal Pronouns

Oral style heavily relies on personal pronouns, most commonly you, we, us, and our.

- Example: In her acceptance speech for the 2015 Goldman Environmental Prize, activist Berta Cáceres says “¡Despertemos¡ ¡Despertemos Humanidad¡ Ya no hay tiempo. . . . El Río Gualcarque nos ha llamado, así como los demás que están seriamente amenazados. Debemos acudir.” (Let us wake up! Let us wake up, humanity! There is no time. . . . The Gualcarque River has called upon us, as have other gravely threatened rivers. We must answer their call.)

Written Style may or may not rely on personal pronouns, depending on the purpose and context of the writing. For example, in a formal research report, there might be more frequent use of third person such as one, they, and he/she/they.

Grammar and Sentence Structure

In oral style, you use shorter thought units that are easy to follow, whether simple sentences or fragments. Thoughts may begin with and, but, etc.

- Example: Ashton Applewhite begins her TED talk “Let’s End Ageism” with a series of questions and short sentences, many starting with and: “What’s one thing that every person in this room is going to become? Older. And most of us are scared stiff at the prospect. How does that word make you feel? I used to feel the same way. What was I most worried about? Ending up drooling in some grim institutional hallway. And then I learned that only four percent of older Americans are living in nursing homes, and the percentage is dropping. What else was I worried about? Dementia. Turns out that most of us can think just fine to the end. Dementia rates are dropping, too. The real epidemic is anxiety over memory loss.”[1]

Written style may or may not use longer and more complex sentences. It’s expected that you follow grammatical rules in writing (unless you are doing creative writing of dialogue).

- Example: “In many modern nations, however, industrialization contributed to the diminished social standing of the elderly. Today wealth, power, and prestige are also held by those in younger age brackets. The average age of corporate executives was fifty-nine years old in 1980. In 2008, the average age had lowered to fifty-four years old (Stuart 2008). Some older members of the workforce felt threatened by this trend and grew concerned that younger employees in higher level positions would push them out of the job market. Rapid advancements in technology and media have required new skill sets that older members of the workforce are less likely to have.”[2]

Repetition

Oral style uses greater repetition of words and phrases to emphasize ideas.

- Example: Winston Churchill, speech to the House of Commons, June 4, 1940: “We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”[3]

Written style: often uses more precise and varied language to repeat ideas.

- Whereas Churchill’s speech uses the verb fight seven times, this excerpt about the Battle of Britain from a biography of Churchill uses a variety of words and formulations to describe fighting. “The Luftwaffe’s [German Air Force’s] first object was to destroy the RAF’s [the British Royal Air Force’s] southern airfields. Had this been accomplished there is no doubt that a seaborne invasion would have been launched with a good prospect of establishing a bridgehead in Kent or Sussex. After that the outlook for Britain’s survival would have been bleak. But the RAF successfully defended its airfields and inflicted very heavy casualties on the German formations, in a ratio of three to one. Moreover, the German aircrews were mostly killed or captured whereas British crews parachuted to safety. Throughout July and August the advantage moved steadily to Britain, and more aircraft and crews were added each week to lengthen the odds against Germany. By mid-September, the Battle of Britain was won.”[4]

Colloquialisms and Tone

Oral style uses a more conversational tone and often uses colloquial/informal words and contractions.

- Example: Simon Sinek, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” said, “As we said before, the recipe for success is money and the right people and the right market conditions. You should have success then. Look at TiVo. From the time TiVo came out about eight or nine years ago to this current day, they are the single highest-quality product on the market, hands down, there is no dispute. They were extremely well-funded. Market conditions were fantastic. I mean, we use TiVo as verb. I TiVo stuff on my piece-of-junk Time Warner DVR all the time.”[5]

Written style may use a more formal tone, depending on the writing’s purpose and context. There usually is less use of colloquialisms and contractions.

- From an academic article about TiVo: “Our analysis of the longitudinal data on TiVo and the TV industry ecosystem generated three themes that we develop in this paper. First, a disruptor confronts three competitive tensions—intertemporal, dyadic, and multilateral. Second, the disruptor continually adjusts its strategy to address these competitive tensions as they arise. Third, as the disruptor’s innovation and relational positioning within the changing ecosystem coevolve, the disruptor has greater latitude to frame its innovation as sustaining the operations of ecosystem members. Overall, these themes contribute to an understanding of strategy as process.”[6]

Vocabulary

Oral style uses simple, familiar words to promote audience understanding.

- Note how Sinek, in the example above, uses everyday words in simple sentences. The thesis of his speech is stated equally simply: “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.”

Written style might use a richer and more precise vocabulary, regardless of audience.

- The academic article cited above uses a number of words most non-expert readers would have to look up to understand. Coopetitive is a made-up word combining cooperative and competition. Intertemporal describes a relationship between past, present, and future events. Dyadic describes the interaction between two things. And multilateral means three or more parties are involved. In a speech—unless it’s a speech to experts—a sentence containing all four of these words will cruise over the heads of most audience members.

Word Choice

A speech must be well researched, logical, and applicable to its audience. These things alone, though, will not guarantee a successful presented in language that’s appropriate to the audience. When choosing wording for your speech, consider the following:

Abstract versus Concrete Words

Abstract refer to intangible qualities, ideas, and concepts that we only know through our intellect, like love, success, moral, or a lot. They are ambiguous; each audience member may hold a different understanding of the same abstract word. Abstract words work best when appealing to or evoking emotion from a large audience. They enable each audience member to relate in their own way. They should be avoided, however, when providing instruction or other instances when detail is necessary.

Concrete words refer to tangible qualities or characteristics, things we can see, smell, touch, taste, or hear. Words such as house, apple, rose, laptop, spicy, and purple are all concrete. Concrete words are definitely needed when your purpose is to explain a process or provide instructions.

Speeches will have a blend of abstract and concrete words. To help audiences emotionally connect, visualize your message, and grasp your meaning, you need to sketch the big picture using abstract words. You also need to share concrete stories and examples to add interest and relate to your audience’s experience. It’s your job as a speaker to determine the level of concreteness needed based on your purpose, audience, and context.

If you feel you need to use more concrete language, you may want to use a process called the ladder of abstraction, which moves a word from general to specific. General words, like jobs, games, or purple become more narrow and precise descriptives when advancing through the ladder, making it easier for the audience to visualize your words.

Ladder of Abstraction Process

Entertainment → Games → Video Games → Multiplayer Online Games → Fortnite→ Fortnite Battle Royale

In the following video, slam poet and activist Kyle “Guante” Tran Myhre talks about the importance of using specific, concrete language. Guante is talking about writing spoken-word poetry, but his points about language apply equally to informative speaking. Especially when we’re speaking to inform, it can be easy to fall into broad or abstract descriptions, which can be confusing or forgettable for audiences. Specific, concrete language, however, is easier to follow and much more memorable.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WxB6PppNtkc

You can view the transcript for “Guante: On Concrete Language, Specificity, and Turning Ideas into Poems” here (opens in new window).

Here is the video with accurate captions: Guante: On Concrete Language, Specificity, and Turning Ideas into Poems (opens in new window).

Jargon versus Familiar Words

Jargon is a form of shorthand that conveys a specific meaning to the insiders who use it. For instance, within some industries, acronyms like ROI, C-suite, API, or BSB are expected to be used and understood, so when presenting within those industries, using that jargon can be efficient and effective. Though it’s fine to use this specialized vocabulary with a group of industry insiders, it can be confusing and isolating for audience members outside the field or industry. When presenting to a mixed audience where some know and expect jargon and others do not, it is helpful to define the jargon or acronym the first time it is used.

When speaking with a general audience, it’s best to use familiar language that is commonplace both to yourself and to your audience. One of the biggest mistakes novice speakers make is thinking that they have to use fancy or very formal words because it makes them sound smarter. Actually, fancy and formal words tend not to work well in oral communication to begin with. Using language that’s not your everyday language will make both you and your audience uncomfortable, and runs the risk of your audience misunderstanding your message. Use words that are easy to understand and recognize.

Word Meanings

Words have both denotative and connotative meanings.

The denotative meaning is the standard, dictionary-based meaning of a word. Be careful of assuming the audience will all assign the same denotative meaning to your words, though. Some words have multiple denotative meanings, such as scale. Therefore, providing context is important.

The connotative meaning is made up of the emotional responses and personal thoughts evoked by a word. Connotations represent various social overtones, cultural implications, or emotional meanings. Different audience members may have different reactions to the same word. Therefore, careful audience analysis as well as others’ perspectives will help you choose your language carefully so as to get the desired reactions to your words.

Language Traps

Language can either inspire your listeners or turn them off very quickly. An important step in revising and refining your speech is to ensure that you’ve avoided any language traps that may cause you to lose your audience.

Exclusionary and Offensive Language

While we tend to think of extreme and obvious language choices such as profanity, racial slurs, and other forms of hate speech when considering this language trap, language is constantly changing to reflect the culture and society that uses it. As a result, some words and phrases that may not have been considered exclusionary or offensive in the past are rightly recognized as such now. As a speaker, it is your responsibility to learn what may be considered exclusionary and offensive before you deliver your speech.

Inappropriate Language

As with anything in life, there are positive and negative ways of using language. One of the first concepts a speaker needs to think about when looking at language use is appropriateness. By appropriate, we mean whether the language is suitable or fitting for ourselves as the speaker, our audience, the speaking context, and the speech itself.

Yourself – One of the first questions to ask yourself is whether the language you plan on using in a speech fits with your own speaking pattern. Not all language choices are appropriate for all speakers. The language you select should be suitable for you, not someone else.

Your Audience – Consider whether the language you are choosing is appropriate for your specific audience. Let’s say that you’re an engineering student. If you’re giving a presentation in an engineering class, you can use language that other engineering students will know. On the other hand, if you use that engineering vocabulary in a public speaking class, many audience members will not understand you.

The Context – Identify what the expectations of communication are in the particular context of your speech. Recall that the speaking context includes the occasion, the time of day, the mood of the audience, and other factors in addition to the physical location. The language you might use in addressing your co-workers may differ from the language you might use at a business meeting in a hotel ballroom. If you’re giving a speech at an outdoor rally, you cannot use the same language you would use in a business meeting. Take the entire speaking context into consideration when you choose language for your speech.

The Speech Itself – Consider whether your language is appropriate for your specific topic. If your speech topic is the dual residence model of string theory, it makes sense to expect that you will use more sophisticated language than if your topic was a basic introduction to the physics of sound waves.

Inaccurate Word Usage

We learn words by experiencing them. Reading words without ever hearing them can often lead to mispronunciation. For instance, words like ennui are often mispronounced. Furthermore, when we learn words by hearing them without ever reading or looking up their dictionary meaning, we sometimes mishear or combine what we hear with what we already know, resulting in embarrassing inaccuracies when we later use that word.

When speakers use incorrect words, it can, at the very least, confuse and distract the audience, and at worst, lower their credibility with the audience. Below are four common ways that speakers use incorrect and inaccurate words.

Words that do not exist – This error occurs when we mishear or combine two words to inadvertently create a new, nonexistent word rather than using the correct word for what we mean. Common examples are conversate and supposably.

Not knowing the definition of a word – This error happens when we only learn a word by hearing it and rather than learning the actual definition. We mistake those common words for the actual word that means what we intend. Common examples are bemused, compelled, travesty, ambivalent, and literal.

Malapropism – A malapropism is the use of an incorrect word in place of a word with a similar sound, resulting in a nonsensical statement. For example, Former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott once claimed that no one “is the suppository of all wisdom” (rather than the repository, or place where things are stored).

Eggcorns – An eggcorn is a word or phrase that results from a mishearing or misinterpretation of another because it sounds similar and seems logical or plausible. An example is the common eggcorn “all intensive purposes” which should be “all intents and purposes.” An eggcorn often involves replacing an unfamiliar, archaic, or obscure word with a more common or modern word. An extensive database of eggcorns is maintained here (opens in new window).

Creating “I versus You” Scenarios

There may be appropriate times to separate yourself as the speaker from the audience, for instance when telling a personal story. Using first-person singular to refer to yourself and second person to refer to the audience throughout the speech, however, creates an I and you that can create a divide between speaker and audience. This is often how experts are disparaged and labeled as “elitist” or “know it all” by the audience. Whenever possible, use the first-person plural, “let’s explore,” “we will,” “our best interest,” to enhance your credibility with the audience.

- https://www.ted.com/talks/ashton_applewhite_let_s_end_ageism ↵

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-introductiontosociology/chapter/ageism-and-abuse/ ↵

- https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1940-the-finest-hour/we-shall-fight-on-the-beaches/ ↵

- Johnson, Paul. Churchill. United Kingdom, Penguin, 2010, 118. ↵

- https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action ↵

- Ansari, Shahzad, Raghu Garud, and Arun Kumaraswamy. "The disruptor's dilemma: TiVo and the US television ecosystem." Strategic Management Journal 37.9 (2016): 1829–53, 1830. ↵